This year brings the first official observation of Indigenous People’s Day in Vermont. It's also a time to reflect on what this part of the world was like before any Europeans set foot here, and on a submerged river bank in Brattleboro, ancient petroglyphs offer a clue.

Petroglyphs are images carved into natural stone. They’re only known to exist in two places in Vermont: one on the shore of the Connecticut River in Bellows Falls, the other in Brattleboro, where the West River and Connecticut meet.

Sketches of those Brattleboro petroglyphs as well as one historic photograph were made in the 1800s. But then the carvings were flooded by the Vernon Dam and buried under a thick layer of silt for more than a century.

Even the precise location was uncertain until very recently, when archaeologist Annette Spaulding found one face carving in 2015, and then what appeared to be a portion of the main panel of petroglyphs in 2017.

It took decades of research and hundreds of dives, but eventually Spaulding found a twelve-by-eight foot ledge with nine petroglyphs. It was under two and a half feet of silt and sand, about 15 feet beneath the water surface in a cove.

“Five thunderbirds, what appeared to be a person, and either a dog or a wolf, and two, what appeared to be eels, like lamprey eels, or snakes,” Spaulding said.

She explained this one late summer day from a pontoon boat on the West River, where others gathered round in kayaks and more people settled on the shore for a discussion of the cultural significance of Brattleboro's petroglyphs.

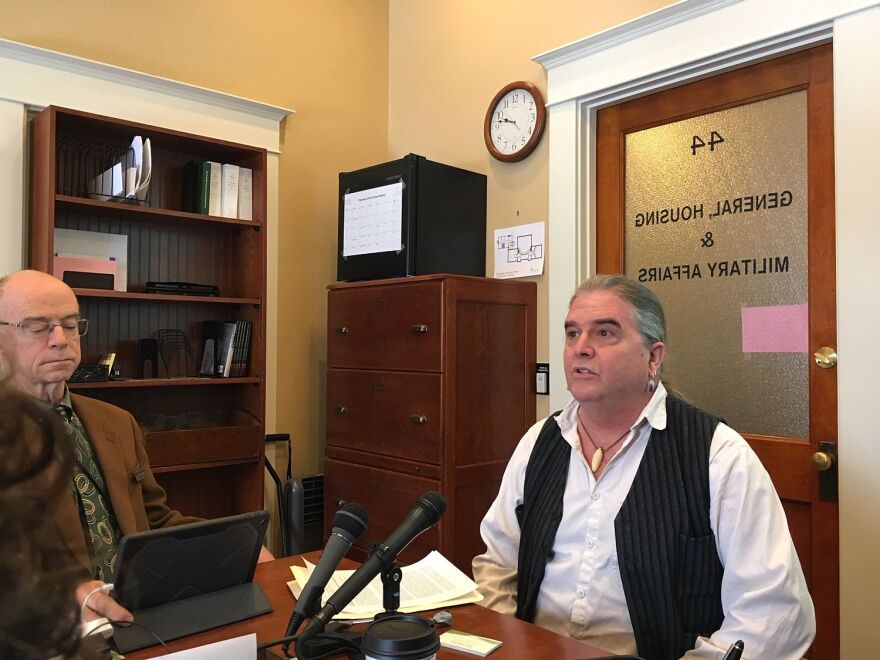

With Spaulding was Rich Holschuh, a member of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs.

"Petroglyphs are not just a billboard in the wilderness. They're in certain places for certain reasons, and that directly informs why they are there, and it's one of the reasons why they are so uncommon. And the fact that they're here tells you that there's something larger going on." — Rich Holschuh, Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs

“Petroglyphs are not just a billboard in the wilderness,” he said. “They're in certain places for certain reasons, and it’s one of the reasons why they are so uncommon. And the fact that they’re here tells you that there’s something larger going on. There’s a bigger story and that story in the case of petroglyphs in the Northeast usually involves a perception of a convergence of worlds, and the spirits.”

It’s easy to see two major rivers, or water highways, converge in the petroglyph area. Less obvious are the two very different geologies of Vermont and New Hampshire that also come together there. The Westminster West fault zone passes directly through the mouth of the West River, right in the same spot.

The historical record also suggests that this is where there may have once been a whirlpool.

There’s mention of one in the handwritten transcription of a long-ago interview with a local who grew up playing in the river. It’s the only reference known of so far, and there’s no sign of a whirlpool today. But if one did exist, it, too, might have silted over as the waters rose with the dam.

Holschuh said Indigenous people have sometimes represented a whirlpool as an underwater being in the shape of a serpent or a panther, and he thinks the petroglyph thunderbirds — creatures of the sky — may have been meant as a kind of cosmological counterpoint.

“And that doesn’t mean they’re good or bad,” Holschuh said. “But since there’s this strong presence of an underwater being in this place, in order to stay in a good relationship with it, you want to make sure that there is ‘the other’ and to bring that into the relationship in an effort to seek balance.”

The Elnu Abenaki have been working with the local Vermont Land Trust office to conserve land near the West River petroglyph sites. The goal is to ensure Abenaki access to the sacred site and protect the land from development.

Clarification 11 a.m. Oct. 17: This post has been updated to reflect that archeologist Annette Spaulding found different petroglyphs a couple years apart, first a carving of a face in 2015, and then a ledge with nine various carvings on it in 2017.